Slow Flight

Slow flight is one of the most important maneuvers when preparing a pilot for landing. It emphasizes the different controls required at lower airspeeds, and therefore is critical in becoming a proficient pilot. This is the first step in being able to land an airplane on your own!

How Slow Flight Works

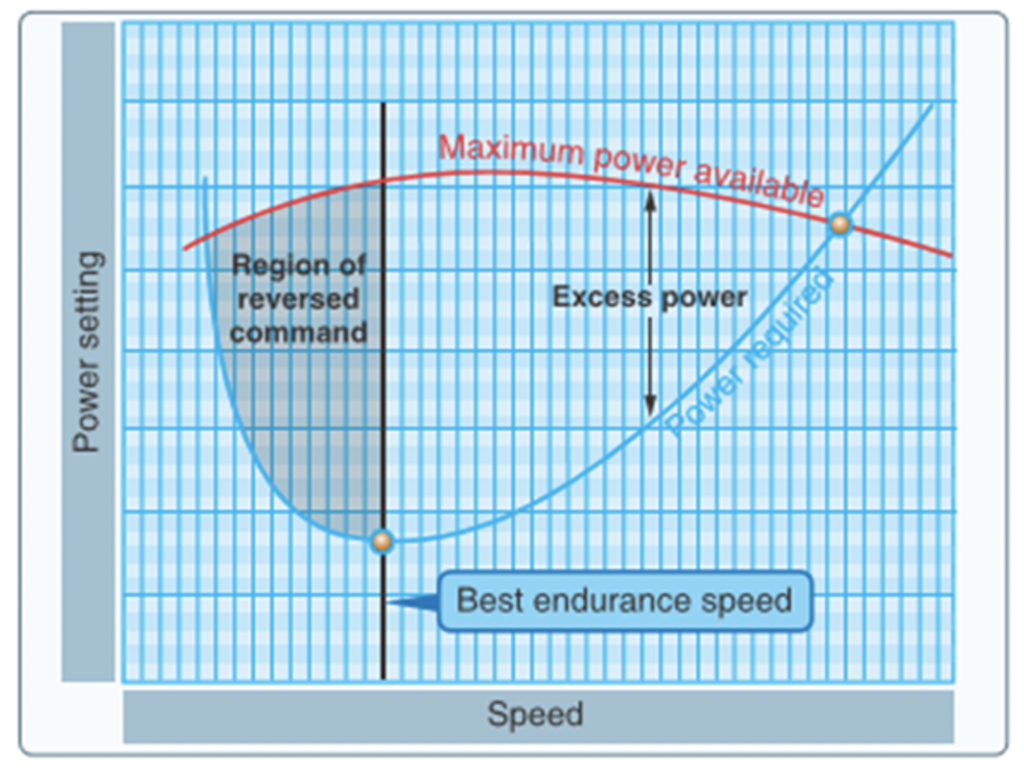

Unlike what you might be used to, slow flight practices flying in what we refer to as the "back side of the power curve." We can see a depiction of this concept in the image below. Once we fall below our maximum endurance speed, the power required to maintain a given airspeed also increases.

Pitch for Airspeed, Power for Altitude

You may have heard this saying before, and it directly applies to slow flight. Conceptually, this might not make sense, so let's try to understand it more. Whenever we are in slow flight, a higher angle of attack is required. Think about it like this: we always need to produce the same amount of vertical lift to maintain level flight, and given that the aircraft is going slow, the only way to maintain that same amount of lift is by increasing angle of attack.

A higher angle of attack, however, is directly related to an increase in induced drag. Therefore, pitching the nose of the aircraft up will technically produce a slight increase in lift, but this is overshadowed by the increase in induced drag, causing the aircraft to slow down. And again, when the aircraft slows down it produces less lift overall.

This is the basis of the saying "pitch for airspeed, power for altitude." Our pitch is mainly used to control the amount of induced drag that we are creating, resulting in airspeed changes, while our power (throttle) can be used to control altitude.

Too slow? Pitch the nose down. Too low? Add power. Too fast? Pitch the nose up slightly. Too high? Reduce power. Remember, however, to always make slight adjustments as small alterations can still result in large altitude or airspeed changes.

Entry into slow flight

Generally slow flight can either be performed with flaps extended or retracted. Your examiner will specify which one to perform, so you should become proficient at performing both. The entry will be relatively similar, with some slight changes. Firstly, select an altitude that allows you to recover above 1,500 ft AGL, and perform the pre-maneuver checklist and make a position report.

Clean Configuration

- Set power to 1200 RPM while maintaining altitude using pitch and allowing the airplane to slow down

- At 60KIAS, set power to 1900 RPM

- Allow the airplane to slow to the target airspeed of 55KIAS

Landing Configuration

- Set power to 1500 RPM while maintaining altitude using pitch and allowing the airplane to slow down

- Add full flaps in steps as airspeed allows, and callout each time you add flaps

- At 55KIAS, set power to 2000 RPM

- Allow the airplane to slow to the target airspeed of 50KIAS

Maneuvering

Now that we have made it to our target airspeed, there are a few things to keep in mind. Firstly, the tolerances for the maneuver do not allow for any airspeed below the target airspeed, so be mindful not to get too slow.

Look OUTSIDE!

Remember, this is a visual maneuver, and you will do the best job if you are mainly looking outside. It can be daunting for the first few times that you do the maneuver, as your airspeed is close to stalling speed, but just remember that you're always welcome to check the altimeter and airspeed. Just don't let that become your main focus. If you focus on getting the correct pitch attitude and power setting, you will do better than if you're stuck inside. Your pitch will roughly resemble a Vx pitch, but as you practice the maneuver make sure to pay attention to where the horizon is so that you can refer to it each time you do slow flight.

Turns

Just like a normal turn, banking the airplane will cause the vertical component of lift to decrease as we exchange it for horizontal lift. This means that all banked turns in slow flight will normally require an increase in power to maintain altitude. Anticipate this when entering into a turn by increasing the power in relation to the bank angle. Also, make sure to not bank the aircraft more than 30 degrees, as increasing the laod factor while near stall speed can be dangerous.

Coordination

The combination of high angle of attack and high power setting will cause left turning tendencies to be increased. Make sure to pay attention to the coordination of the airplane throughout the maneuver, and remember that even left turns may require a small amount of right rudder.

Climbs and Descents

Just as we discussed above, our primary method of controlling altitude in slow flight is with power. This means that initiating a climb will mainly come down to increasing the throttle, while initiating a descent will mainly come down to decreasing the throttle. Even so, pay close attention to your pitch and airspeed and make adjustments as necessary to stay on your target airspeed while changing altitude.

Exiting the maneuver

To exit, add full throttle while controlling the pitch to maintain altitude. If performing the maneuver in the clean configuration, simply maintain altitude until cruise speed is attained and return to normal flight. In the landing configuration, after adding power set flaps to 20 degrees, then 10 degrees as airspeed passes 60KIAS, and finally 0 degrees as airspeed passes 70KIAS. Be sure to call out all flap changes and the airspeeds that they occur at.

After returning to cruise airspeed, be sure to complete the cruise checklist.

Common Errors

Below are many common errors that occur when performing slow flight. Be sure to review them to make sure that you are not making the same mistakes.

- Failure to adequately clear the area

- Inadequate back-elevator pressure as power is reduced, resulting in altitude loss

- Excessive back-elevator pressure as power is reduced, resulting in a climb followed by rapid reduction in airspeed

- Insufficient right rudder to compensate for left yaw

- Fixation on the flight instruments

- Failure to anticipate changes in AOA as flaps are extended or retracted

- Inadequate power management

- Inability to adequately divide attention between airplane control and orientation

- Failure to properly trim the airplane

- Failure to respond to a stall warning

A Few Extra Notes

Sometimes slow flight can be intimidating. Understanding how it conceptually works, however, can make it a lot easier. Also remember why we are learning it in the first place: to be able to land the airplane! Ask your flight instructor if there is something you don't understand or if you feel uncomfortable performing the maneuver, they are there to help you.

Completion Standards

Performance of maneuvering during slow flight is required on both the private and commercial practical tests. However, the commercial ACS requires a tighter tolerance, which is displayed below:

Knowledge

"Aerodynamics associated with slow flight in various airplane configurations, to include the relationship between angle of attack, airspeed, load factor, power setting, airplane weight and center of gravity, airplane attitude, and yaw effects."

Risk Management

- Inadvertent slow flight and flight with a stall warning, which could lead to loss of control

- Range and limitations of stall warning indicators (e.g., airplane buffet, stall horn, etc.)

- Failure to maintain coordinated flight

- Effect of environmental elements on airplane performance (e.g., turbulence, microbursts, and high-density altitude)

- Collision hazards, to include aircraft, terrain, obstacles, and wires

- Distractions, loss of situational awareness, or improper task management

Skills (demonstrated)

- Clear the area

- Select an entry altitude that will allow the Task to be completed no lower than 1,500 feet AGL (ASEL, ASES) or 3,000 feet AGL (AMEL, AMES)

- Establish and maintain an airspeed at which any further increase in angle of attack, increase in load factor, or reduction in power, would result in a stall warning (e.g., airplane buffet, stall horn, etc.)

- Accomplish coordinated straight-and-level flight, turns, climbs, and descents with the airplane configured as specified by the evaluator without a stall warning (e.g., airplane buffet, stall horn, etc.)

- Maintain the specified altitude, ±100 (private) / ±50 (commercial) feet; specified heading, ±10°; airspeed, +10/-0 (private) / +5/-0 (commercial) knots; and specified angle of bank, ±10°.